Fast Food

In March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we successfully rolled out our newly adapted digital programme and launched our Renfrewshire-wide emergency response. At STAR Project we pride ourselves on our ability to be flexible, creative, and responsive to the needs of our community. If ever there were an opportunity to demonstrate this, it has been during the pandemic. We worked with 10939 people during 2020, an increase on the previous year of over 600%.

We knew we could not close our doors to the public until we had implemented all the support they required beforehand. It took us less than 36 hours to convert our programme onto online platforms. The team brainstormed ideas, trialled different interfaces, and settled on the most accessible and creative tools to engage our community. By the end of day two, we were confident that we had effectively reproduced our entire programme digitally. In addition to the digital programme, we also replicated our popular one to one support sessions with wellbeing calls. This meant, for community members who could not or would not access the internet, there was still support in place for them.

With our contingency plan fully operational, we were able to close our building to the public without losing engagement from the community. However, there was one outlier to our contingency plan that could not be replicated digitally – our Community Fridge and Pantry (CFP.) Since its launch in March 2019, our CFP had been well utilised by both our regular community members as well as the wider community. For many, it acted as a vital lifeline, offering a stigma free solution to food insecurity.

We pondered the impact of stopping access to the CFP and wondered if it would be easier to simply signpost community members to the Foodbank instead. The answer was not difficult. STAR, after all, is not in the habit of removing things, especially in a time of crisis and uncertainty. We concluded the safest, most effective answer was to convert the CFP into a delivery service. Ensuring that those most in need of food and essentials, had easy access to it.

In keeping with our stigma-challenging ethos, we never collected names for the fridge. We kept a tally to report on fridge usage but did not want people to have to tell us why they were accessing it. That conversation, we felt, was best initiated by the community member. Whereby, if they felt safe enough to tell us they were struggling, we could signpost them to an advice service or work on a one to one basis with them.

We cannot overemphasise the feeling of fear and panic that permeated the air in March 2020. We knew, prior to even considering converting the CFP into a delivery service, our meagre surplus food would not be enough to sustain the community. We acknowledged the need for fresh fruit and vegetables to be made available. Staples such as bread, dairy products, meat and fish were important. We were vehement that we would not provide people with rations. At no time during the pandemic was there an actual shortage of food, despite perceptions, so we were determined to give people a choice in the foods they received. Now, perhaps more than ever, when choices felt restricted, the least we could do was give people the dignity of choosing what they needed.

Personal hygiene products were vital too. No one will forget the debacle of people panic buying toilet rolls at the start of the pandemic. They may have reconsidered if they could hear our frantic community members describe what they had to resort to in the absence of toilet roll. On more than one occasion, we heard community members cry with relief when we assured them we could provide them with this basic household item. The same can be said of sanitary products. We have been running period poverty campaigns for many years at STAR. Giving access to free products and challenging stigma associated with it. This only benefited us during the pandemic, we were not afraid to ask people if they required them. More often than not, these had been the first items to be ‘sacrificed’ in place of food.

Importantly, and at the request of the community, we sourced pet food. Something, they said, that other places hadn’t considered. Many of our members told us ‘I don’t care about me; I’d go hungry if it means I can feed my pet.’ We were determined that neither was acceptable and began asking for pet food donations. By listening to our community members, being led by them, we were able to provide meaningful support. We did not simply want them to survive, we wanted them to be comfortable, safe and know that we were there.

We quickly established food partners, over 100 in total! St Mirren Charitable Trust, already a partner in our Paisley Men’s Shed, reached out early and began a public campaign to get members of their fan base to donate. They enlisted their corporate partners to act as a conduit between us and local supermarkets. There were several organisations helping us in the early days, but without a doubt, SMCF was the most responsive. ‘The Saints’ as SMFC referred to them, were indeed just that. Each time we got close to running out of food, there would be a knock at the door and the fans would be there, bags in hand. They’ll never know the full extent of the energy and hope they brought to us.

We were also fortunate to benefit from a partnership with Morrisons Anchor Mills. Their Community Champion had seen our work and was keen to support it. What began as a one off, large donation, quickly developed into a weekly food run. Morrisons showed us that their commitment to their community was not tokenistic. With each donation we were humbled, grateful and motivated to keep going. We were experiencing partnership working in a way we never had before.

Professional partnerships are not dissimilar to personal ones. It’s vital that everyone involved is respectful of each other. Communication is key and the need to be explicit about expectations is often an uncomfortable conversation but one that is needed at the start. Some of the partners from the early days of the pandemic fell away. We would not drop our standards and asked the same of them. It may have seemed unreasonable that, during an emergency, we insisted on not taking food that we would not eat ourselves (e.g. flattened bread, packaged items with tears, food that would not last beyond one day.) If we wouldn’t take it, the partners said, they knew plenty of places that would - they were welcome to it. We believe it was these high standards that meant statutory services referred to us, safe in the knowledge that we had robust procedures and systems in place. Whilst we were disappointed to lose partners, we were quickly able to find new ones that absolutely adhered to our standards without question. Demanding? Yes, unapologetically so. In a time where it would have been easy to do something that ‘would do’ – we knew it wouldn’t do for us.

As the pandemic progressed, there were many emerging groups establishing themselves and we knew this access to ‘free food’ would be open to exploitation, cynical as it may seem. Most people feel tremendous embarrassment about reaching out to ask for food, but a wily few were often able to access multiple food sources throughout the pandemic. We were keen to negate this and tried to link with as many groups as possible. The benefits of this were twofold. One, we were able to share resources which were quickly depleted with the creation of the new groups and two, we were able to discuss areas we were covering. We gladly stepped aside from delivering in an area that was covered by a local group. At STAR, we acknowledge that the Place Based Approach is an important one. No one knows their community better than a group embedded there. We saw patterns of behaviour from individuals who were accessing multiple resources and, whilst being mindful of GDPR, we were able to respectfully mitigate this and ensure they were only accessing one group. The important lessons we had learned from years of partnership working came to the fore and, collectively, we were able to find solutions to some of the barriers to working with individuals in crisis.

We had always prided ourselves on not collecting names and addresses for our pre-COVID CFP, but this was no longer possible. We needed to know who needed the food and where it was going. We never asked why but we did check if they were accessing any other support. We quickly pulled together a database. Somewhere to analyse the data, a record of food insecurity during a pandemic. After the pandemic subsides, it will serve as tool to pinpoint the key factors involved in food insecurity. Establishing the database and the prerequisite paperwork felt like a lot at the time, but it has enabled us to keep partners continually updated, to feed into strategic policies and, perhaps most importantly, it has assisted us to see where individuals would benefit from more in-depth support due to their frequent access of the CFP. We are able to quickly notice patterns in data. i.e. busy days, times correlating with new restrictions being published. Having the data at our fingertips has enabled us to keep an overview of demand in Renfrewshire. We believe, irrespective of emergency need, the planning and preparation that goes into creating a service like this is vital. Without this, the service is unlikely to be sustainable and runs the risk of not supporting the people accessing it in the way they require.

Once we got news out to the community about our emergency food response, the phones started ringing almost immediately – they never stopped! The questions we asked people were straight forward. Along with their demographical information, we asked if they were accessing any other supports and spoke to them about other services we were providing. Where appropriate, we insisted on speaking to the person who needed the CFP. This way, we got to know the person. Again, our person-centred approach came to the fore. By seeing the person as more than someone just needing food (which almost never presents itself on its own) we were able to effectively use our wrap around service to support them. Individuals regularly (in excess of 3 times a month) accessing the CFP at the start of the pandemic have now decreased. This is not because food insecurity has eased, it is because we were able to support the underlying issues. Food insecurity is a symptom of a larger issue and by getting to know the person, you can effectively tailor supports to them. Whether that be benefits checks, signposting to advice agencies or simply providing them with a listening ear. We know our CFP model is effective because of the positive destinations of the people accessing it.

On the first day after closing our building, we had one CFP volunteer. We closed on the Wednesday, began the service on the Thursday, by Friday we had over 30 offers of volunteers. It was humbling. This number grew to well over 100 as the pandemic progressed. Similar to our partnerships, we had a high standard we looked for in our volunteers. This was more than met. We quickly established a team of incredible volunteers, turning up every day to deliver food. In many cases they would source food in their free time. We formed quite a bond. They were forgiving of frantic, exhausted staff sending them around Renfrewshire. The first few weeks, we worked night and day, over the weekend. It was relentless, exhausting but we could see it was working. The people in most need of the food were reaching out and we were relieved we could support them. After all the preparation, the late nights pulling our hair out over paperwork, we saw evidence that developing the service was absolutely the right thing to do.

We adapted our CFP nearly a week before official lockdown. Other than the Foodbank, no one else, that we were aware of, was providing food at this time. It meant the volunteers travelled miles in those early days, out to villages and other towns. It’s very different now as more groups began covering their own area. But we’ll never forget the willingness of the volunteers to get food out. They were understanding of our strict PPE policy and adhered to it to the letter. They faced being stopped multiple times by police for traveling during lockdown, made themselves available from first thing in the morning to last thing at night. If the pandemic had increased the feeling of hopelessness and fear, the volunteers fought this with optimism and selflessness.

STAR has always relied on volunteers, we couldn’t do what we do without them, the pandemic was no different. Similar to pre-COVID volunteer recruitment, we spoke with the volunteers before they started. We wanted to work with their strengths and support their weaknesses. Many volunteers changed their tasks as the pandemic progressed, it was important to be flexible to their needs. We checked in with them daily, volunteering during the pandemic took its toll on everyone’s mental wellbeing. We ensured we revisited policy and procedures with them regularly. It is easy to become complacent as time progresses, but we knew we could not afford to do this.

In those early, frantic days of the pandemic, it was easy to lose sight of the bigger picture. We were concerned we would become so entrenched in the day-to-day operations that we would not have time to step back and ensure we were looking to the future. This was another luxury we could not afford. The moment a community development organisation stops being responsive and starts being reactive, the community suffers. We needed to take a step back and be reflective. We hired a new member of staff, whose role was to coordinate the CFP. This enabled us to realise that we needed to focus on the next stage. What would happen after the clear and present danger had abated? We knew, with the increase of free food provision, community members could develop a dependency on this. Encouraging learned helplessness is anathema to STAR Project and it was vital that we acted early to circumnavigate this. We acknowledged that not everyone accessing the CFP was experiencing financial difficulty, they were simply unable to leave their house due to shielding or self-isolating. In response to this, we developed STAR Shoppers. A service whereby volunteers would go to a supermarket for someone and buy what they requested. The person could pay either by cash or by contactless card machine. If, during the shopping, the volunteer was unable to get the food they requested, they would phone them to ask if they would like a substitute. Like the CFP, people had the choice they felt they were lacking and quickly the service proved popular. Especially given that delivery slots from supermarkets were few and far between. In addition to giving people who could pay for food the opportunity to do that, it also meant we could support some of our frequent users of the CFP to use it. They gave us their list of foods, if we had it in the CFP, we would add this item at no extra cost. It felt like a gentler introduction into accessing paid food again.

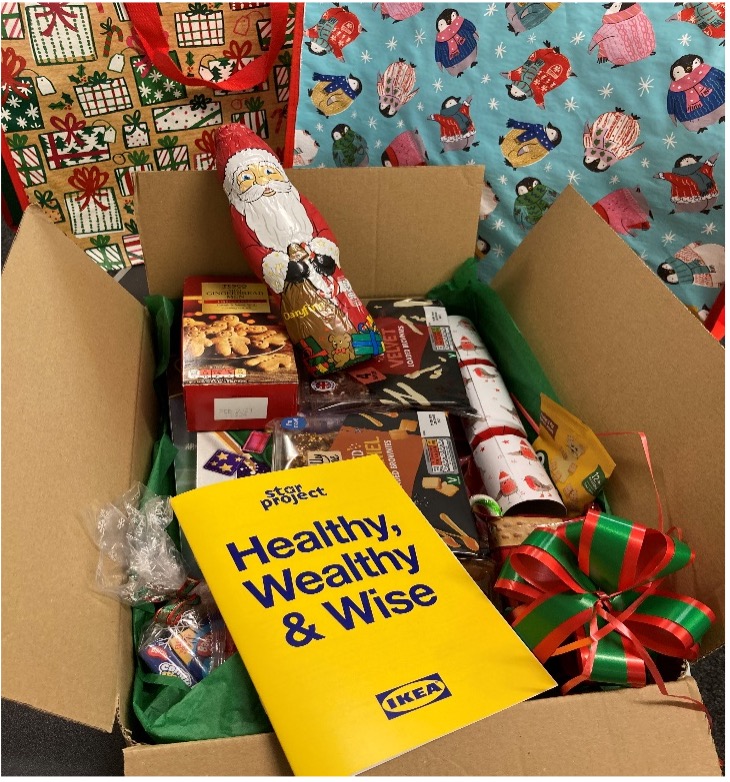

With the increased interest in STAR Shoppers, we realised that the community was keen to be more resilient. We began introducing more supports into our programme to foster this. We developed an initiative, called Healthy, Wealthy & Wise (HWW) where we taught people to cook from scratch. We provided people with cooking videos, a step-by-step cookbook and all the prerequisite ingredients (and, where needed, cooking implements.) We were able to demonstrate that cooking healthy nutritious food from scratch was not only easy, but far cheaper than pre-cooked ready meals. Again, the response to this was better than we had anticipated. We realised we had moved from the hectic days of just getting free food to people, it wasn’t enough. One of our objectives at STAR is to support people to seek their own solutions to issues they are experiencing. Our food reliance campaign does just that. Galvanised by the success of STAR Shoppers and HWW, we are continuing to offer food support with resilience underpinning everything. We are confident that this will ultimately lead to the community feeling more supported and confident in their ability to tackle food insecurity.

Normality, or something like it, feels a long way off. Increased threats to the wellbeing of the public appear to still be in the headlines daily. However, by relying on the framework that STAR has utilised for years, we feel confident that we are in a position to not just support the community through and beyond this crisis, but to encourage them to seek new opportunities and keep themselves safe.

Heather Kay, Project Coordinator

Updated: April 13, 2021